In late February of 1935, the first name of the upcoming Gaumont British Picture Corporation production of, The Tunnel (AKA: Transatlantic Tunnel or Trans-Atlantic Tunnel), was announced: Conrad Veidt.Then in early April, Richard Dix and Madge Evans were added into the mix for this odd sci-fi film. Evans was chosen to play Ruth McAllan, wife of, engineer, Richard McAllan (Dix) the brains and steely resolve behind the transatlantic tunnel; what part Veidt was to portray we may never know for sure but the character of Frederick Robbins, eventually played by Leslie Banks is a significant role and that may have originally been intended for Veidt. In addition, C. Aubrey Smith, contracted with Gaumont for the trans-Atlantic subway movie.

Richard Dix (a favorite of this reporter) sailed for London for filming of the futuristic flick on Wednesday, June 5, 1935; contrary to contemporary reports his wife Virginia did accompany him to England, even though the couple had just had twin boys on May 8.The shooting schedule was set for six-weeks, and even as Dix sailed Conrad Veidt was still listed as a member of the cast of, The Tunnel. Principal filming was finished by the middle of August, although Richard and Virginia Dix would not return to the States until near the middle of September, arriving in Canada, having sailed from France.

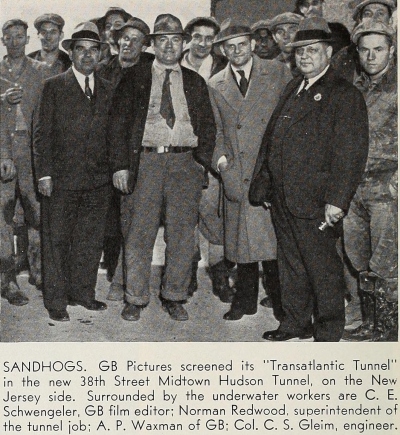

To continue the theme of the, Transatlantic Tunnel, Gaumont British held a screening of the movie in the newly constructed 38thstreet Midtown Hudson Tunnel, on the New Jersey Side, with Gaumont dignitaries in attendance.

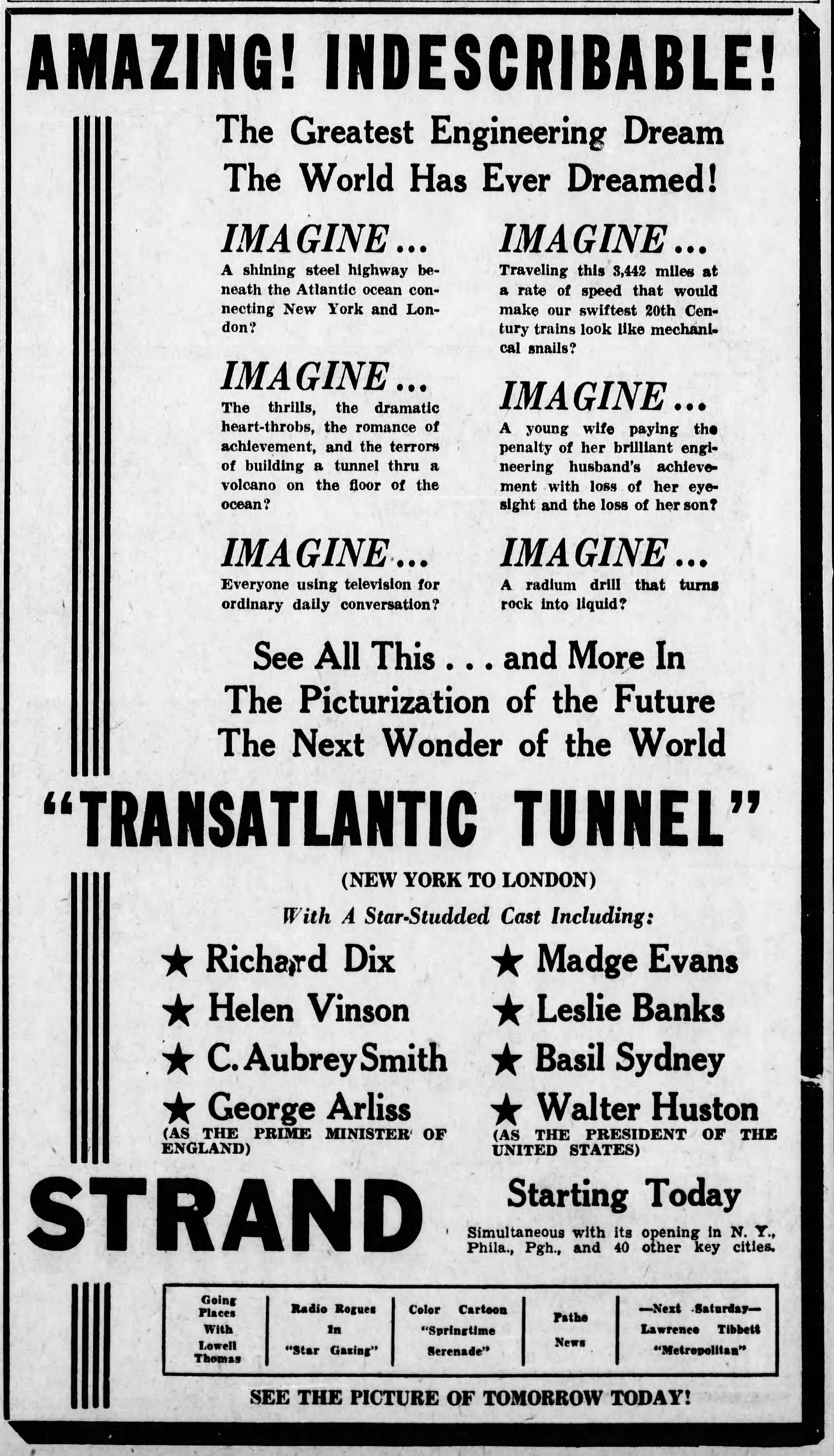

The official release date fixed by Gaumont was October 27, 1935, and the advertisements agree with this. A print of the film was not even in the States until the week of the 13th of October, 1935; Gaumont British sent, Transatlantic Tunnel, from London to Quebec via sea by the Empress of Britain, then a Dominion of Canada mail plane picked up the print and, Transatlantic Tunnel was flown to Quebec City and from there another plane was chartered to Newark, New Jersey. Evidently the air-transport landed with little fuel in the tank, making the tarmac just in time. Once safely on the ground, the next stop was the laboratory for additional prints to be made and finally into the hands of the premiering theaters.

The Roxy was the venue for the, Tunnel, New York opening, with a vital cross-promotion with Philco Radio. The agreement included window displays in 1,500 stores which carried the Philco brand, along with cooperative newspaper adverts. Also in the Philco-Transatlantic tie-in was a special-trailer preceding each showing and a space in the Roxy lobby for a display. More than forty cities were selected by Gaumont to be part of a simultaneous opening, with Los Angeles, Long Beach, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, Sacramento, Fresno and Stockton taking the honors for the West Coast; South Bend, Fort Wayne and Terre Haute, Indiana, Huntington, West Virginia, Cincinnati, Ohio, Louisville, Kentucky, Butte and Great Falls, Montana, Fort Worth and Austin, Texas, Altoona and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Buffalo, New York, Worcester, New Bedford and Springfield, Massachusetts, Portland, Maine and Racine, Wisconsin to name some of those municipalities to host the first-run of, Transatlantic Tunnel. All reports from the Film Daily of box-office receipts for Tunnel, showed success, big-time achievement, and in some cases breaking recent-history house records and being held over was the norm.

Der Tunnel, written by Roman von Bernhard Kellermann and published in 1913, was a hugely popular novel and saw five incarnations on celluloid, beginning with two silent versions, The Rail Line Under the Ocean (with Kurt Matull at the helm), Der Tunnel, in 1915 (directed by William Wauer); then the twin productions of, Der Tunnel and Le Tunnel, each directed by the same man (Curtis “Kurt” Bernhardt), utilizing the same sets, and the same crew, excepting each project had a different editor. Der Tunnel was clipped by Gottlieb Madl and Le Tunnel had the scissors applied by Rudi Fehr; Der Tunnel, premiered in October of 1933 and Le Tunnel, opened in December of ’33. The only actor to appear in both of the 1933 productions was Gustaf Gründgens as Mr. Woolf, the syndicate director.

Not long after, Le Tunnel, was seen, Gaumont British Picture Corporation announced that it too would bring the “story of tomorrow, today,” to the silver-screen. Gaumont intended to use 3,000 extras for the production and insuring that the film would be elaborate in its film-making values. Kurt Siodmach (Siodmak), and engineer was brought on to the project to add a flavor of authenticity, not only working on the story but also providing service as supervisor with director Maurice Elvey. Siodmak had begun writing for film in 1929, but this was his second pen job. He and his wife Erna (they married in 1931) were reporters in Germany, in the mid-1920s; but Kurt’s initial profession had been that of engineer, which led to his work in the fantasy, horror, and sci-fi genres, gaining him positions on projects with a technically bent plot, these mostly, thrillers or actioners. Siodmak offered his thoughts on the scientific aspects of the story, presenting logical, albeit imaginary solutions to the inherent problems with tunneling under the bed of the Atlantic Ocean. His statement shows the depth to which his preparation took him with regards to the mechanics, logistics, feasibilities and the resulting effects of the combination of the sciences needed for such a tunnel building scheme; I have provided Mr. Sidomak’s thoughts in their entirety, in the following attachment.

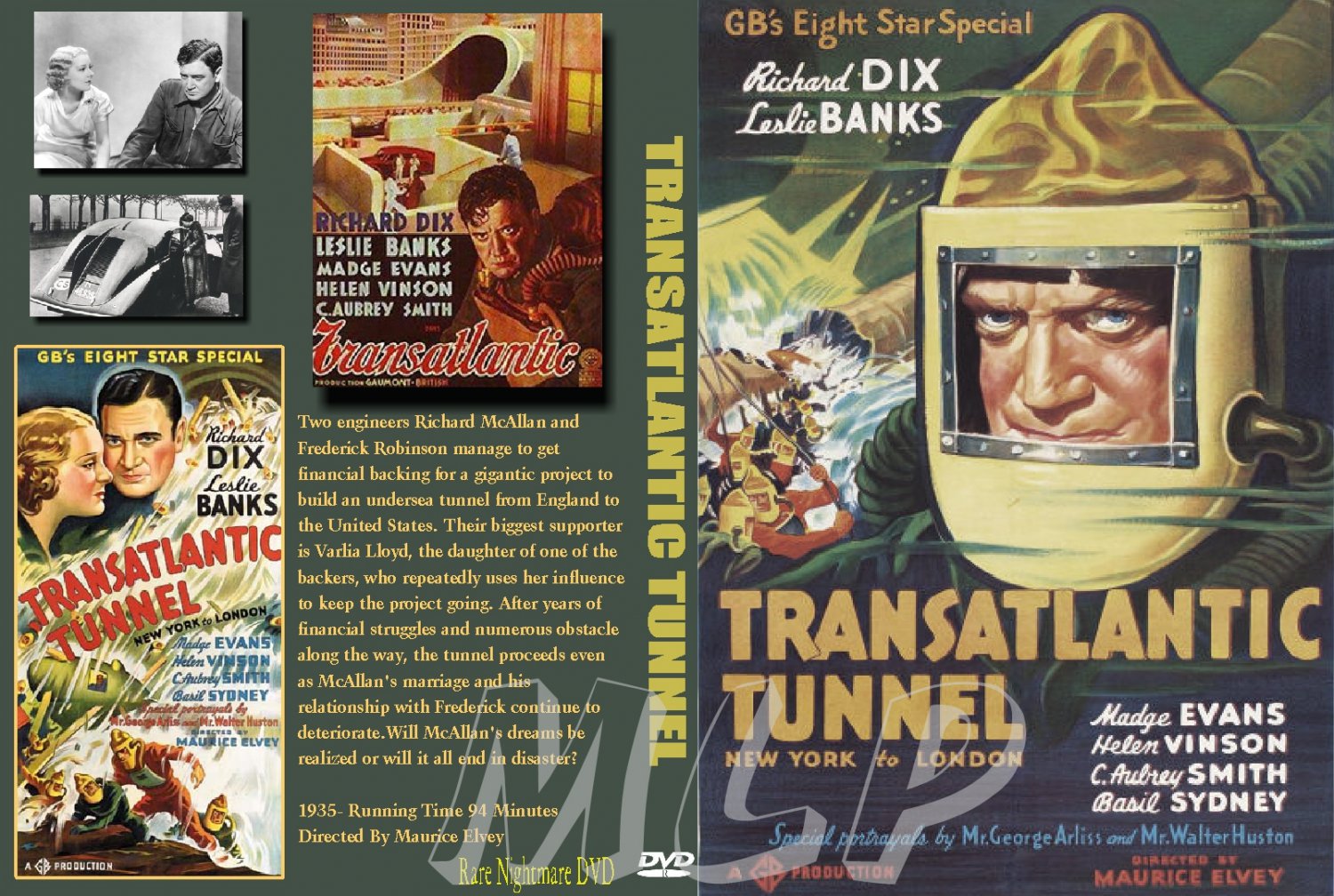

The Transatlantic Tunnel is available for viewing online at archive.org; there is a DVD of, Transatlantic Tunnel (what the quality is I do not know) and can be found on several lesser known sites of which I at all times caution, buyer beware; one such outlet that carries the movie is, The Film Collectors Society of America. Transatlantic Tunnel seems to make an appearance on TCM about once a year, if you are willing to wait.